Artificial Intelligence (AI) is transforming the way we observe, model, and understand our planet. At the center of this shift are foundation models — large neural networks trained on huge, diverse datasets.

These models represent a breakthrough beyond deep learning architectures and mark the beginning of a new era in AI: machines that don’t just analyze data, but learn underlying mechanisms and build a foundation for many other applications.

The evolution of AI models - from machine learning (ML; feature-centric) to deep learning (model-centric) to foundation models (data-centric). The data-centric approach prioritizes the accumulation of large-scale, high-quality data and, where feasible, aims for end-to-end learning. Image source: DATAFOREST

In this first part of the series, we look at what foundation models are, why they matter, and how they are advancing research across the Earth system.

What Are Foundation Models?

If you’ve used tools like ChatGPT, Google Gemini, Midjourney, or GitHub’s Copilot, you’ve already interacted with foundation models. These are large AI systems built at such scale that they consume a nontrivial portion of the world’s electricity, and we’re even at risk of running out of publicly available internet data to train them1.

Foundation models incorporate complex algorithms and deep learning techniques, allowing them to learn patterns, contexts, and nuances from massive and different types of information (also known as modalities) and apply that knowledge to a wide range of tasks.

A modality is a distinct source of data that conveys information in a unique way – for example, images, audio, text, or time series.

Because of this broad training, one model can do many things. For instance, the same AI that helps you draft an email can also:

- Summarize long articles,

- Translate text between languages,

- Generate realistic images from prompts.

Definition: Foundation models are neural networks – trained on extremely large and diverse datasets, generally with self-supervised learning at scale – that can be adapted to accomplish a broad range of downstream tasks.

Their remarkable adaptability and versatility are what set foundation models apart from earlier, task-specific AI systems.

One Model, Many Skills

For years, AI systems were built like a collection of single-purpose tools. One translated text. Another recognized faces in photos. Yet another analyzed weather patterns from radar and satellite imagery. Each was useful – but anytime a new task came along, we had to build and train a new model from scratch, which quickly became inefficient.

Foundation models flip the script. Instead of learning one task at a time, they learn general skills that transfer to many situations.

Think of learning to cook as an example: instead of memorizing every individual recipe, you learn the basics – how to chop ingredients, how flavors work together, how heat changes food, and what spices to use. Once you understand those fundamentals, you can create new dishes without starting from scratch.

Traditional ML vs Foundation models. Traditional ML models are designed to do one specific task. In contrast, a foundation model can centralize the information from all the data from various modalities. This one model can then be adapted to a wide range of downstream tasks. Source: Adapted from Armand Ruiz.

Foundation models learn in a similar way. By training on broad and diverse datasets, they pick up general patterns and develop flexible skills that can be applied to many different problems. That’s why we call them “foundation” models – their broad knowledge becomes the base for countless applications.

Once pre-trained, foundation models can be further fine-tuned or even prompted to tackle a wide variety of tasks – including many they were never explicitly trained to perform.

Pre-train: learn the basic skills from massive datasets (initial training phase)

Fine-tune: customize those skills for a particular task (additional, fast training)

Prompt: use natural language to direct a model to perform a new task without retraining it

Broadly speaking, this flexibility enables AI that grows with our needs – expanding skills as new challenges arise.

Self-supervised Learning

One of the key innovations that makes foundation models possible is self-supervised learning (SSL). Instead of relying on expensive human-generated labels, SSL lets models learn directly from raw, unlabeled data by creating their own training signals. This approach gives foundation models broad exposure to real-world information and helps them build a surprisingly deep understanding of world knowledge.

Self-supervised learning: a ML approach in which a model learns from unlabeled data by generating its own supervisory signals, often by predicting missing or transformed (e.g., masked, shuffled) parts of the input.

We generate overwhelming amounts of unlabeled data every day: text, satellite imagery, sensor signals, and more. Manually labeling it all isn’t just costly – it’s unrealistic. SSL flips this limitation into an advantage by learning straight from the data itself.

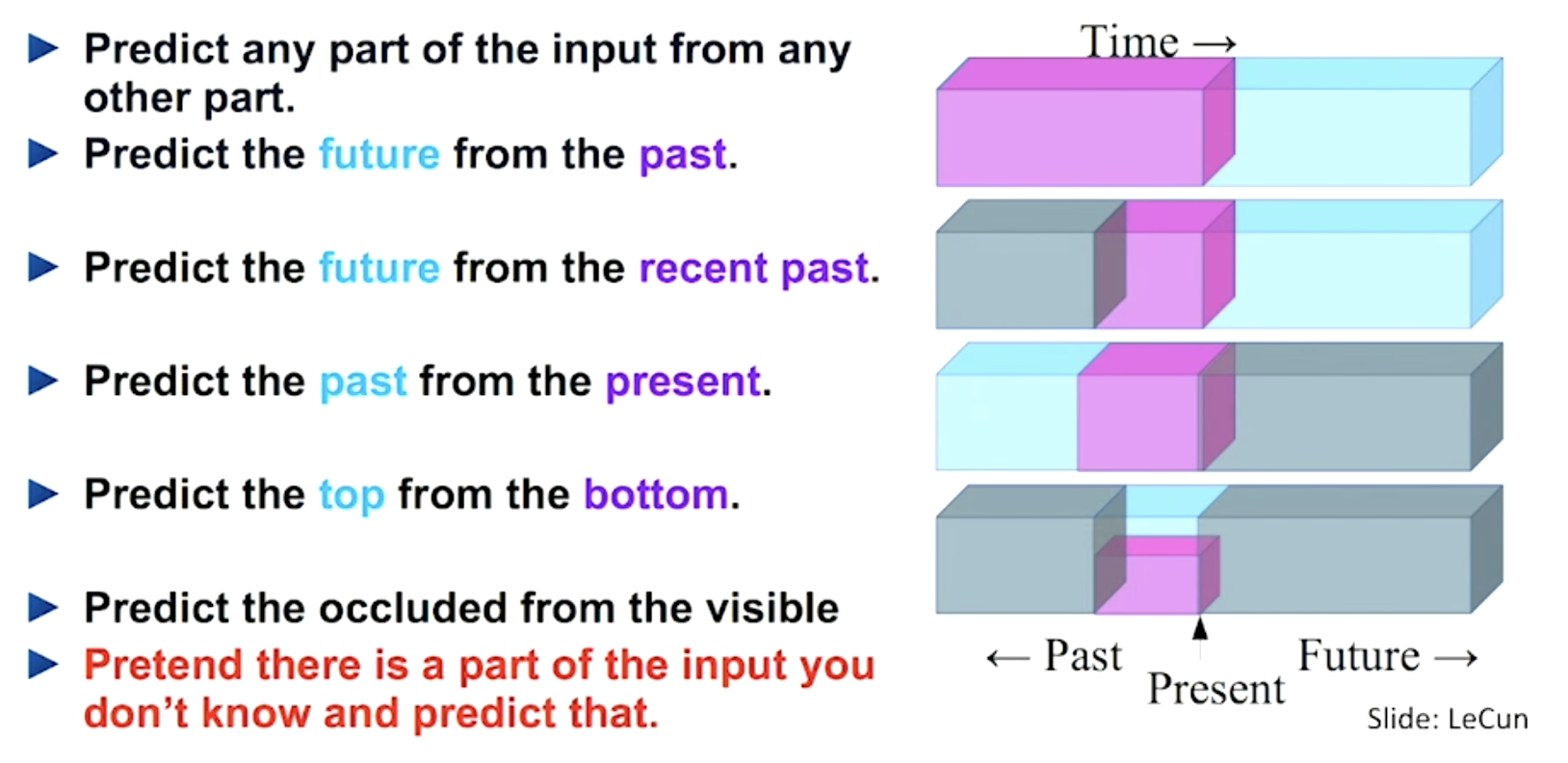

An example of how self-supervised learning tasks can be constructed for text data. Image source: LeCun’s talk.

In essence, SSL transforms an unsupervised problem into a supervised one by generating its own “training signals”. The model sets its own objectives, teasing patterns, structures, and relationships out of massive datasets that would be impossible to label manually.

SSL gives these models the broad exposure they need to generalize across tasks — a capability that has quietly become one of the most important drivers of modern AI.

For a more detailed, mathematical perspective on self-supervised representation learning, see this post from Lil’Log2.

Scale and Homogenization

What makes foundation models so powerful, however, is scale. When we train a model on diverse datasets using large amounts of compute, the model doesn’t simply memorize information – it starts to uncover deeper structures and relationships in the data that generalize beyond what it has seen.

“If I could use only one word to describe AI post-2020, it’d be scale.”– Chip Huyen (AI Engineering)

Pre-training pipeline diagram of foundation models. Image source: Sebastian Buzdugan.

As models scale up, their abilities tend to improve. But at sufficiently large scales, we often see something unexpected: new capabilities appear that weren’t directly targeted during training. These emergent behaviors can include reasoning in unfamiliar situations, integrating patterns across different modalities, or detecting subtle signals that humans might overlook.

Emergent behaviors: characteristics that arise from the interactions inside a large system – not explicitly programmed, and not visible in smaller models.

Together, large-scale training and SSL transform AI models from narrow tools into flexible, general-purpose systems. This also leads to an important outcome: homogenization.

Homogenization: the process by which AI systems across diverse tasks and domains converge toward a shared set of large, general-purpose model architectures, training objectives, and data sources — reducing variation in design and increasing reliance on common computational infrastructure.

In the past, every scientific task required its own specialized model. If you were predicting wildfires, forecasting air temperatures, or estimating crop yields, you’d build everything from scratch – new architecture, new data pipeline, new rules. Each domain built and maintained its own datasets and assumptions.

Homogenization changes this paradigm. A single foundation model can serve as a shared computational “backbone” that many applications and research areas build upon. Instead of numerous disconnected systems, we get a unified base that becomes more capable as more users contribute data, insights, and fine-tuned adaptations.

The result is less fragmentation across the scientific landscape and more opportunities for collaboration. As foundation models continue to scale, they increasingly serve as shared infrastructure – a general foundation that supports progress across diverse domains.

Now, these AI models are being applied to one of the most complex systems: our planet.

Foundation Models for Earth System

Dynamic One-For-All (DOFA) - A unified multimodal foundation model for remote sensing and Earth observation. Image source: Xiong et al., (2024)

Earth foundation models (EFMs) bring the principles of foundation models from language and vision AI to the study of our planet. Instead of learning from books, websites, or photographs, EFMs are trained on massive collections of geoscience data: satellite observations, climate simulations, weather sensor networks, ocean measurements, and more.

EFMs will help bridge the gap between observation and understanding the Earth system – enabling faster science and more informed actions in a rapidly changing world.

By learning from this rich and multimodal data, EFMs can develop a holistic view of processes that shape Earth’s systems, such as:

- How weather patterns form

- How the oceans and atmosphere interact

- How environmental changes unfold over time

It is important to note that an EFM typically doesn’t cover the entire scope of Earth science at once. Most EFMs are built for a specific domain such as Earth observation, climate modeling, biodiversity, or land use. Still, the knowledge they gain often transfers across applications, giving scientists and users a flexible base to build upon.

| Category | Scope | Training Data | Example Models |

|---|---|---|---|

| Geospatial | Earth observation | Satellite & aerial imagery, GIS, etc | DOFA3, Prithvi4, Clay5, TerraMind6 |

| Climate | Modeling, downscaling | reanalysis, ESM outputs, atmospheric data, etc | Earth-27, ClimaX8, Aurora9, ORBIT-210 |

| Environment | Environmental monitoring | Fire data, hydrology, soil moisture, precipitation | Granite-Geospatial-Ocean11 |

| Biodiversity & Ecosystem | Species & habitat monitoring | Camera traps, lidar, bioacoustics, etc | NatureLM-audio12 |

An EFM that covers all major components of the Earth system in a single, unified framework would be considered a General Earth Foundation Model (GEFM)$^\dagger$. Reaching this milestone would represent a significant step forward for Earth science – but we are not there yet. We will explore the path toward such a model in a future post.$^\dagger$This concept reflects the author’s emerging perspective and is shared to encourage discussion rather than imply consensus.

Like other foundation models, EFMs are pre-trained on enormous datasets and then fine-tuned for specific applications. This reduces the time, cost, and expertise required to build advanced models from scratch, helping accelerate research, integrate knowledge across domains, and provide a flexible foundation for tackling complex Earth science problems.

Why Foundation Models for Earth System?

Our planet is complex and changing rapidly, and the pace of those changes demands faster, more integrated science. Weather extremes, ecosystem shifts, rising sea levels – none of these exist in isolation. They are interconnected parts of a single, complex system.

However, traditional modeling approaches often treat them separately because each domain requires its own tools, data formats, and expertise. That separation makes it harder to understand how different parts of the Earth interact, such as:

- How drought influences wildfire behavior

- How ocean warming affects coastal storms

- How land-use change affects regional climates

EFMs are important for efficiency, generalization, and innovation.

EFMs help bring these pieces together, supporting efficiency, generalization, and innovation. Because they learn from broad and multimodal datasets, EFMs can uncover relationships that span different scientific fields. For example, a model trained on atmospheric data can benefit from what it learns about land or ocean processes. It can generalize to new locations, new time periods, and sometimes new types of data.

While the initial investment to develop an EFM can be substantial, the long-term benefits are immense. Utilizing pre-trained foundation models significantly speeds up and reduces the cost of developing new ML applications compared to training custom models from scratch. This provides a significant opportunity:

- Smaller teams can access capabilities that once required massive resources

- Scientists can focus more on discovery and less on building infrastructure

- Early-warning systems can update more frequently with richer information

- Decision-makers can gain clearer insights from a unified view of Earth

Ultimately, EFMs reduce the time between observing a change and understanding what it means – and that speed matters when lives, ecosystems, and economies are at risk.

Challenges and Limitations

Building EFMs pushes the boundaries of both AI and geoscience – and doing so comes with major challenges:

Scale and Infrastructure: Developing an EFM from scratch requires significant resources, time, and coordination across institutions. This includes expensive hardware, massive amounts of data, and months of training.

Data: Earth science data is not evenly distributed. Observations in the Global South, oceans, and polar regions remain sparse, while many datasets lack long historical records or consistent quality. Models inherit these gaps, which can lead to biased predictions in places where insights are most urgently needed.

Bias, Uncertainty, and Error Propagation: Flaws in pre-training can silently scale across every downstream application. Transparent evaluation, benchmarking, and uncertainty quantification are essential but not yet standardized.

Cross-Domain Expertise: EFMs sit at the intersection of advanced AI and Earth system science. Combining these disciplines demands specialized knowledge that remains scarce and unevenly accessible.

Summary

- Foundation models represent a major shift in how AI learns — from task-specific tools to flexible, general-purpose systems.

- EFMs apply these advancements to geoscience, learning from massive, multimodal datasets across the Earth system.

- Once pre-trained, EFMs reduce the time and expertise needed to build powerful models for specific applications — accelerating research and decision-making.

- Challenges remain, including compute demands, uneven data coverage, and the need for responsible governance to ensure equitable benefits.

In Part 2, we’ll dive into how foundation models are used in Earth sciences.

References

Huyen, C., 2024. AI Engineering: Building Applications with Foundation Models. O’Reilly Media, Incorporated. ↩︎

https://lilianweng.github.io/posts/2019-11-10-self-supervised/ ↩︎

Xiong, Z., et al., 2024. Neural plasticity-inspired multimodal foundation model for earth observation. arXiv preprint arXiv:2403.15356. ↩︎

Szwarcman, D., et al., 2024. Prithvi-eo-2.0: A versatile multi-temporal foundation model for arth observation applications. arXiv preprint arXiv:2412.02732. ↩︎

Clay Foundation Model. https://clay-foundation.github.io/model/ ↩︎

Jakubik, J., et al., 2025. Terramind: Large-scale generative multimodality for earth observation. arXiv preprint arXiv:2504.11171. ↩︎

Earth-2. https://www.nvidia.com/en-us/high-performance-computing/earth-2/ ↩︎

Nguyen, T., et al. (2023). ClimaX: a25 foundation model for weather and climate. In Proceedings of the 40th International Conference on Machine Learning (ICML'23), Vol. 202. JMLR.org, Article 1078, 25904–25938. ↩︎

Bodnar, C., Bruinsma, W.P., Lucic, A. et al. (2025). A foundation model for the Earth system. Nature 641, 1180–1187. ↩︎

Wang X., et al. (2025). ORBIT-2: Scaling Exascale Vision Foundation Models for Weather and Climate Downscaling. In Proceedings of the International Conference for High Performance Computing, Networking, Storage and Analysis (SC ‘25). Association for Computing Machinery, New York, NY, USA, 86–98. ↩︎

Granite-Geospatial-Ocean. https://huggingface.co/ibm-granite/granite-geospatial-ocean ↩︎

Robinson, D., et al., 2024. NatureLM-audio: an Audio-Language Foundation Model for Bioacoustics. arXiv preprint arXiv:2411.07186. ↩︎